Hannah Richards

Artist || Teacher

Small-city stock. Biology researcher. Doula. Security guard. Curator. Wife. Mother. Art teacher from kindergarten to the undergraduate level. With this variety of experiences both past and present, how does Hannah still find the time to be an artist? Her story is a perfect case study, and refreshing evidence that the othereight can apply even when you’re not a carefree, single, urban professional.

To this point, we have defined our othereight as the shift away from the traditional 9-5, a diversification of time. But it is equally true as a diversification of place. Nowadays, city dwellers desire more and more to get out of their congested homes. It’s actually an age-old trend that’s finding new life in the 21st century. Hannah has been in the robust Western Massachusetts art scene for a while. In it, she sees an increase in people doing part-time or multiple jobs at once. The quintessential abandoned barnhouses that pepper the New England countryside are being renovated, and artists are often the first ones to take advantage, transforming them into studios and event spaces. Real estate is cheaper and overhead is smaller (in Hannah’s case, literally: she works under the sloped ceiling of her house’s attic in Greenfield). Recognizing the trend, municipalities and arts foundations offer numerous grants. In smaller towns and communities, it’s easier to connect to one another, to the landscape, and to your work. You sense you can make something on your own.

I ask Hannah how she even finds time for work with teaching and family in the picture. “My time is increasingly not my own,” she admits, so she must stay organized. Typically, she finds time to sneak up to the attic on weekends, but she works best in dedicated blocks of time, so she must constantly seek out residencies. She is currently at a two-week residency at Mass MoCA. The time in between she calls “percolation time,” building and filtering ideas and observations, and it can last from a month to a few years, so she has to balance short-term alertness with long-term planning. “For me, it’s been so helpful to orient my perspective toward the long game,” Hannah says. Being an efficient observer takes practice, too, like her 10 years working as a security guard at The Smith College Museum of Art. “Talk about percolation time,” she says. Hannah has even worked as a doula, assisting new mothers and helping them build their relationship with their child. It taught her the importance of generously giving time to others to build relationships.

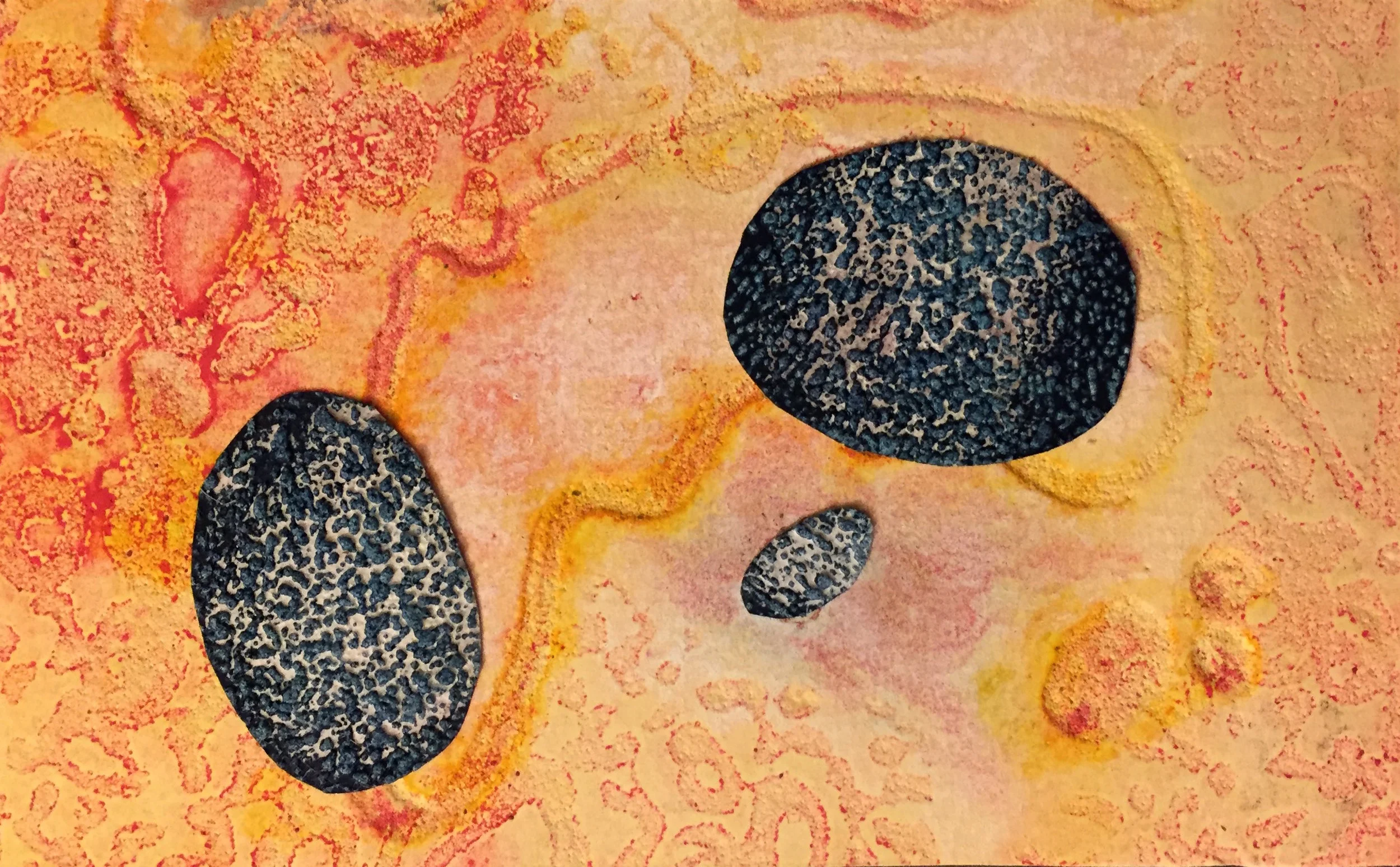

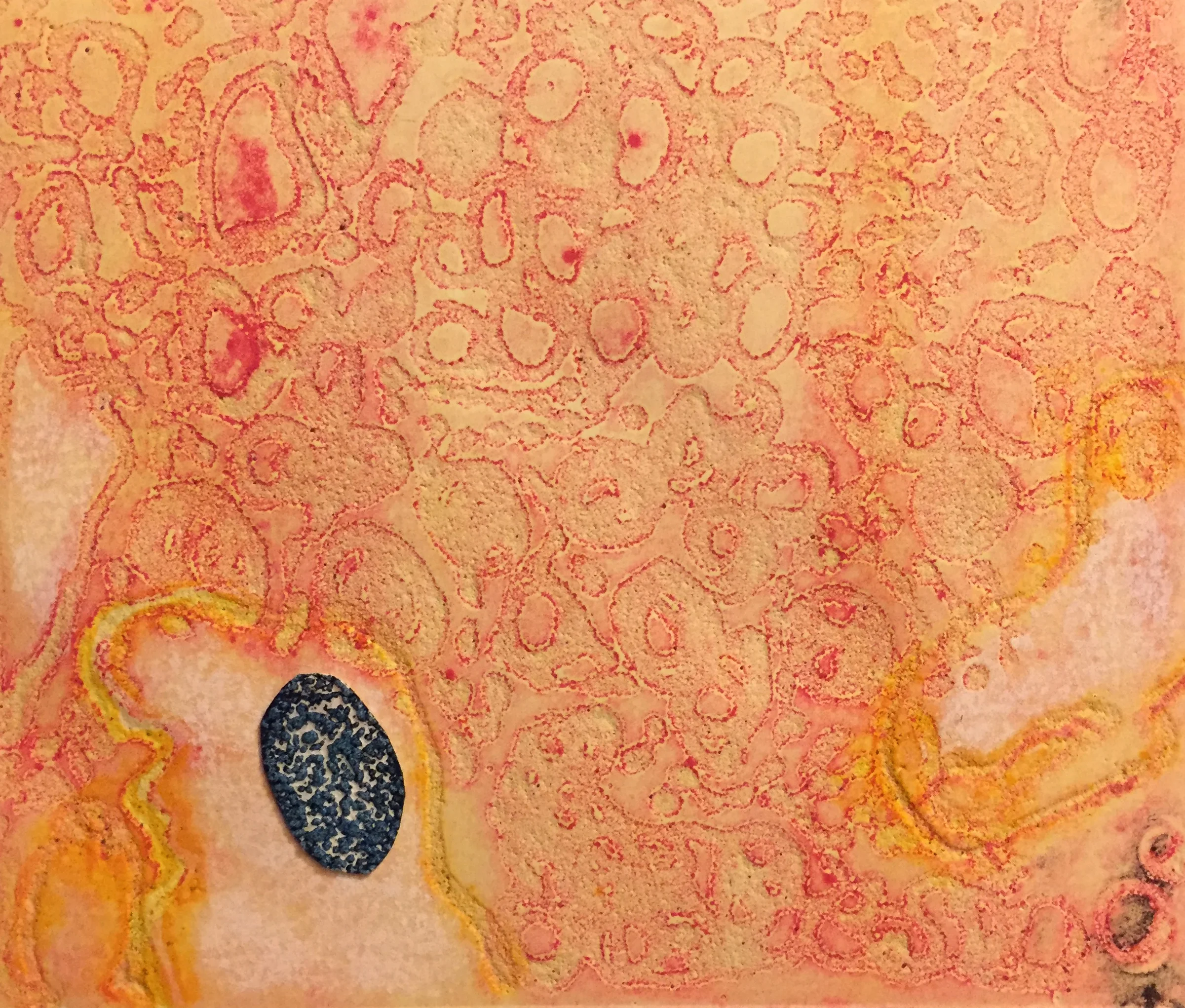

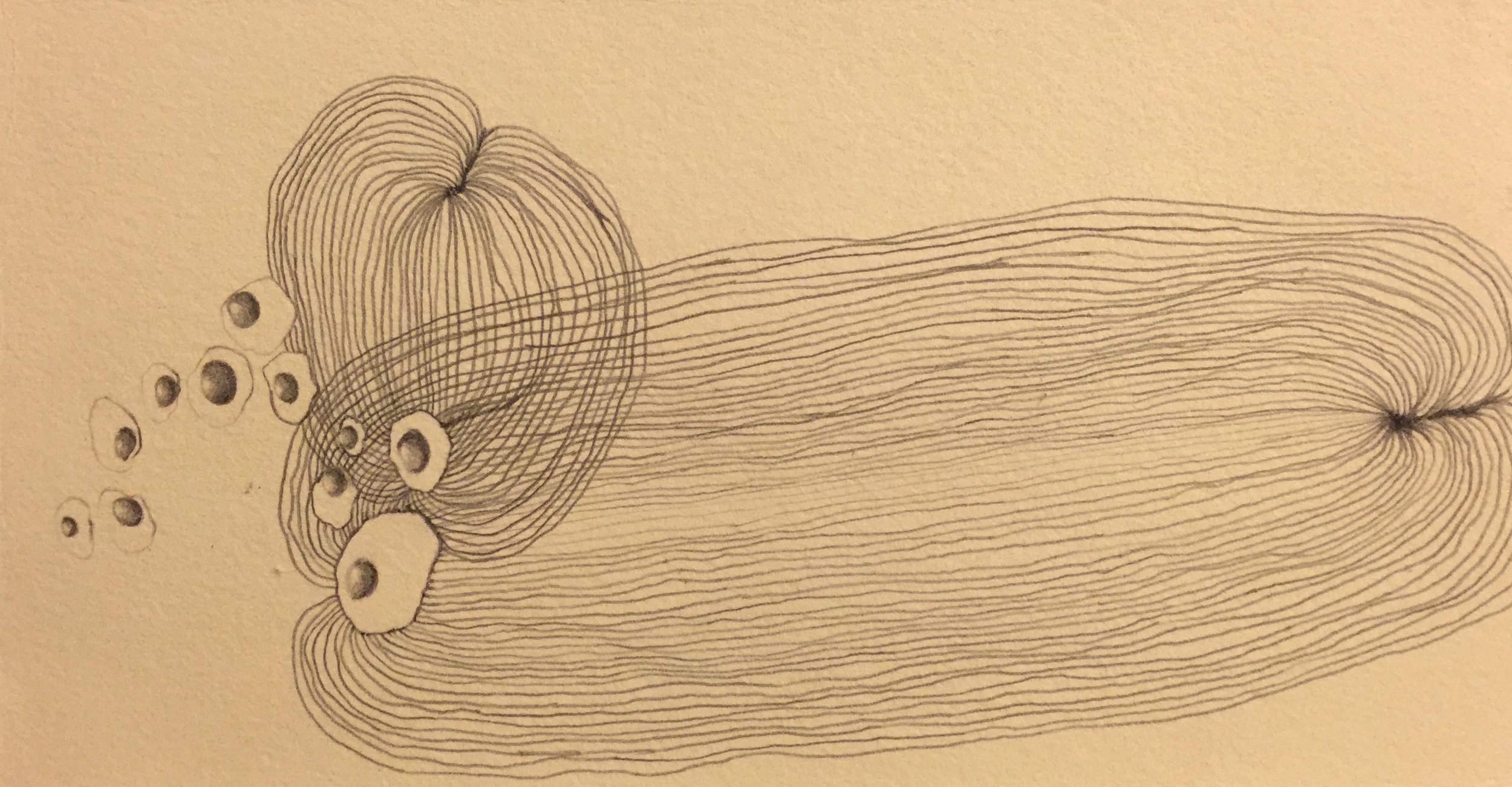

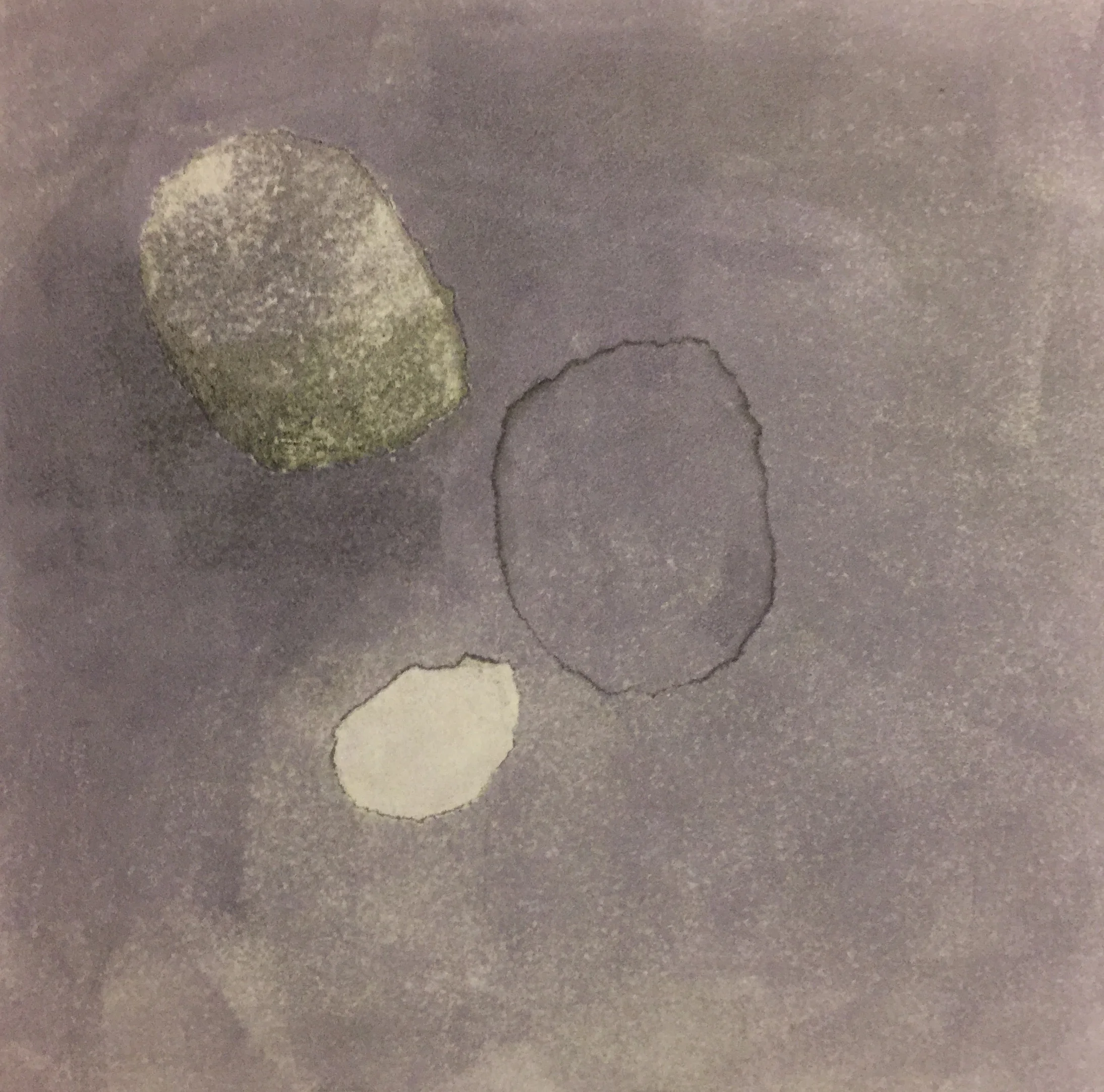

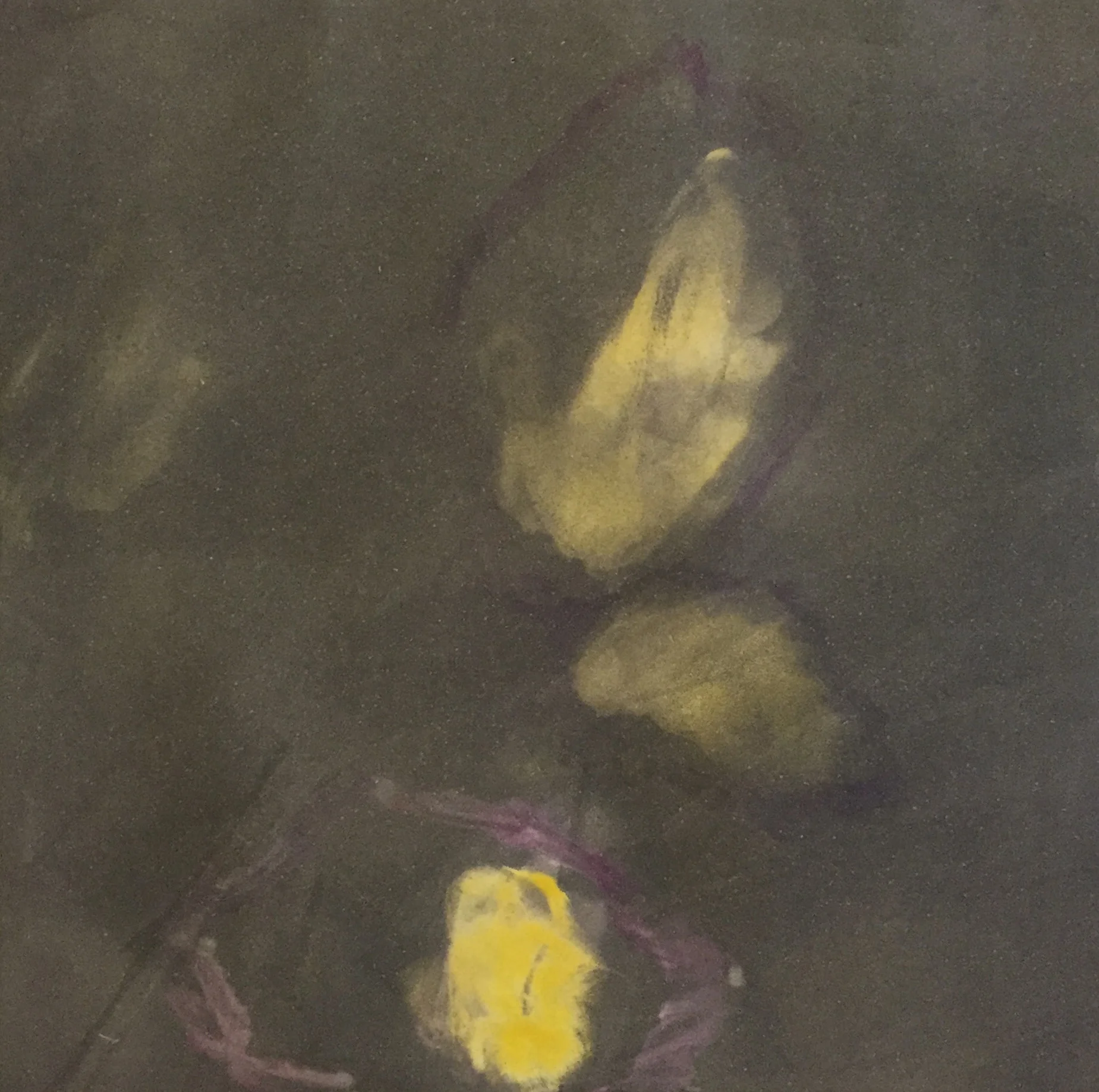

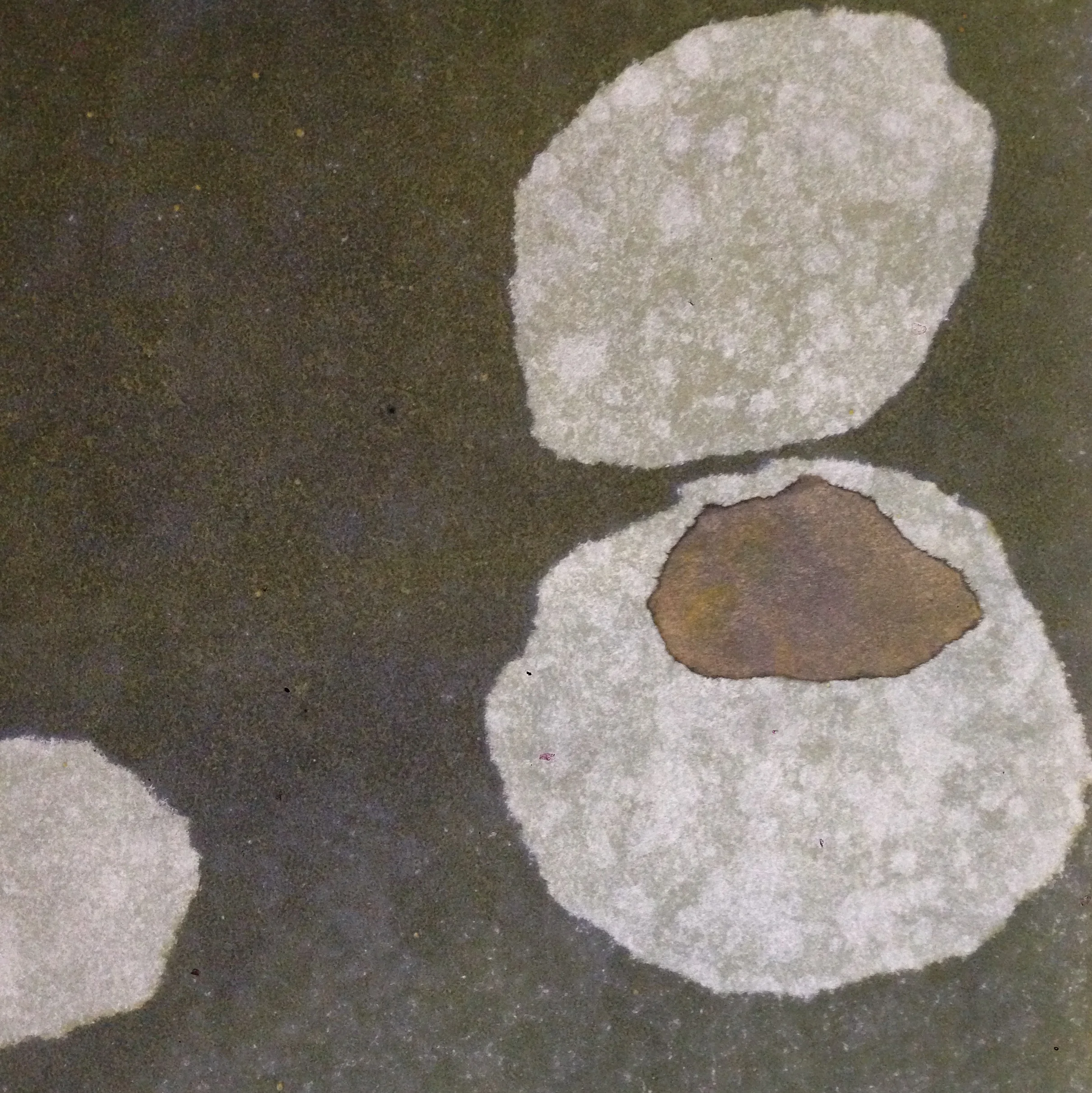

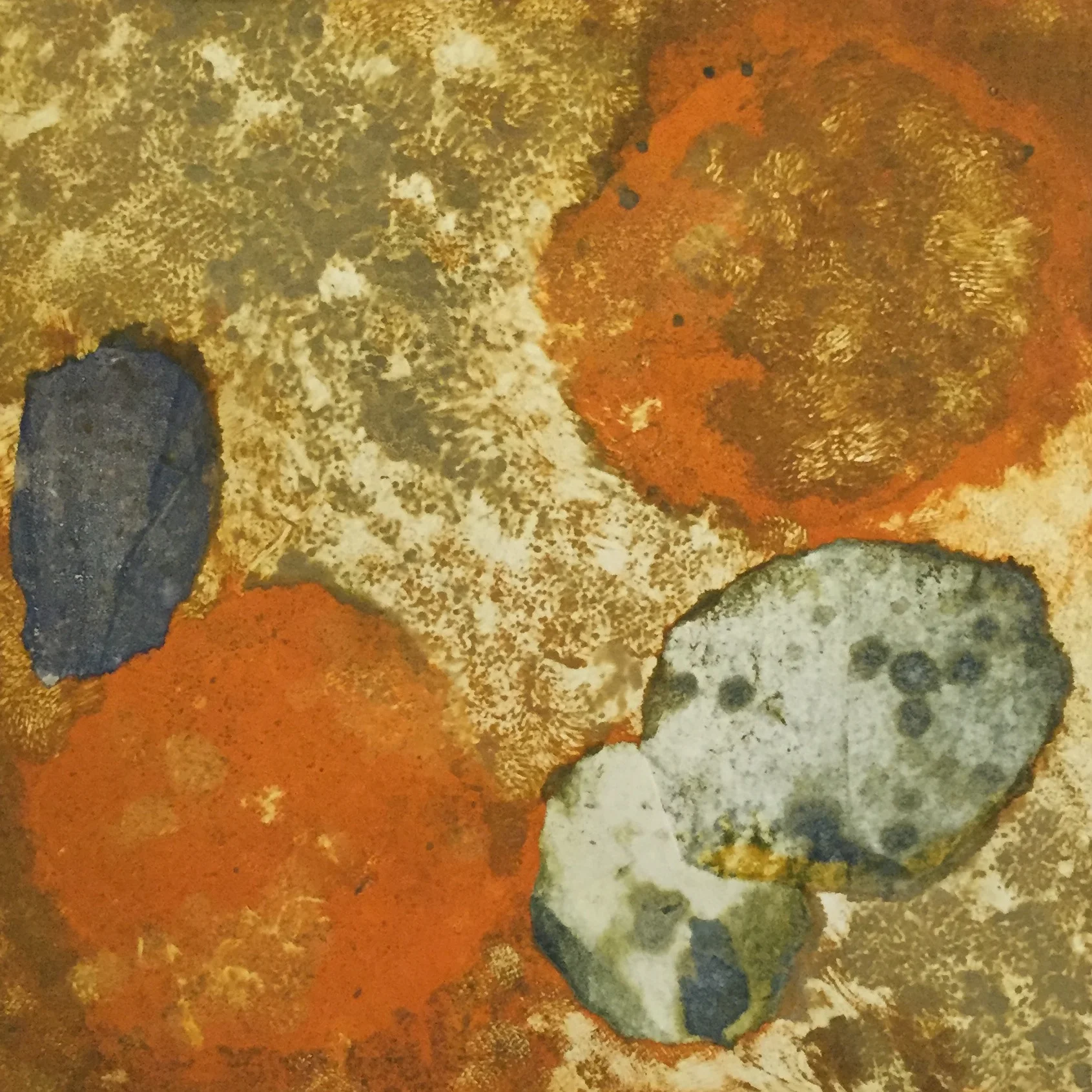

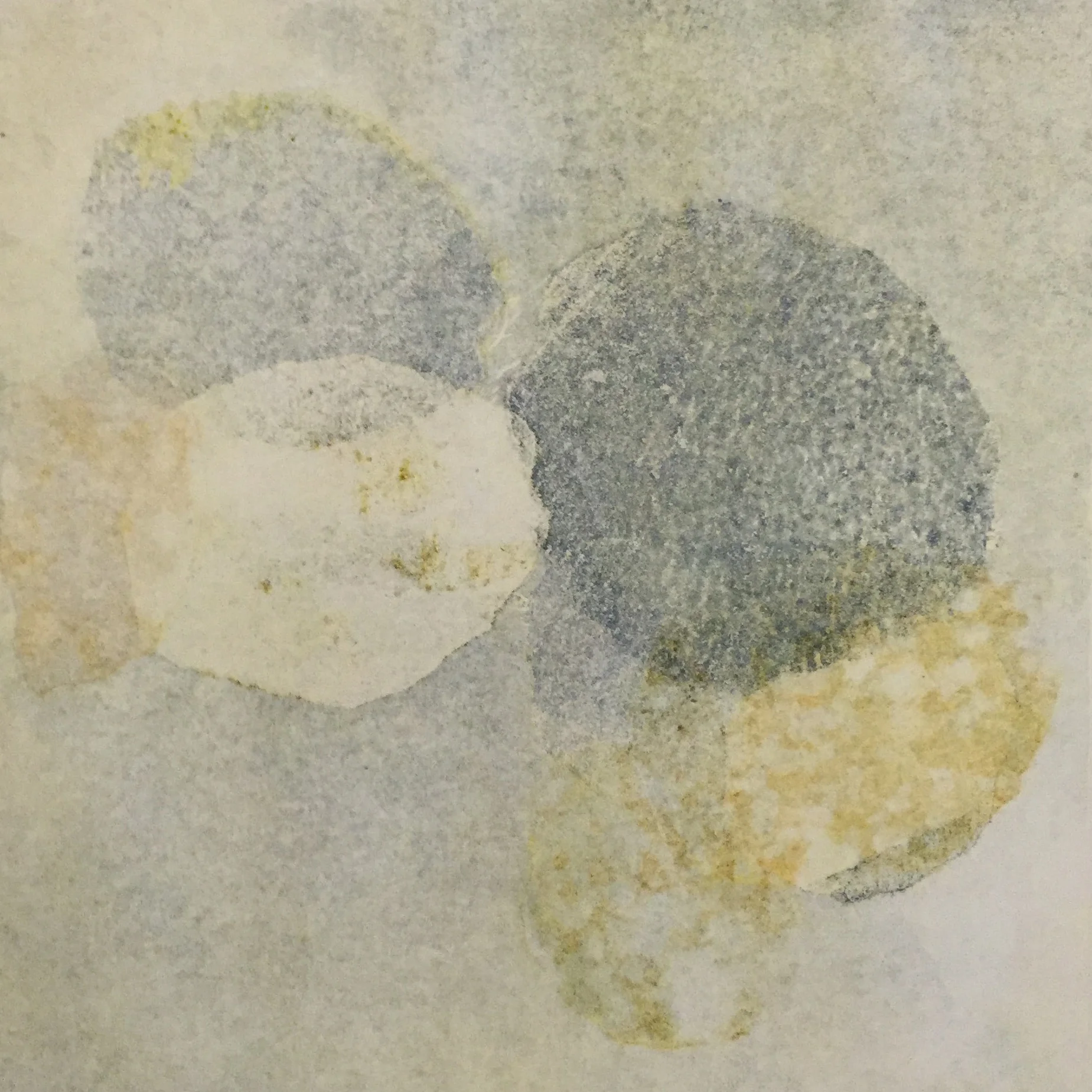

Hannah sees her artwork as another process of nature. With that mindset, she stays open to all sorts of influences. For instance, in college, she was pushed by a biology professor to apply for a research grant (which she received) to study methods of photographing biofilm. Many of her collographs are reminiscent of looking under an electron microscope. “I think the scientific method has a big influence on my work. I think the artist’s process is about devising and pursuing experiments….” Hannah found extra time to experiment in her B.A. program at Smith College because she had accelerated through foundational painting and drawing courses in high school. She only returned to them once she started teaching, and was rediscovering the basic media along with her students. She recalls while teaching chiaroscuro, the kids were more interested in the technique and process of layering paint than they were in the final effect (which is how art undergrads first learn about it). I asked if the idea to use Elmer’s glue was inspired by the classroom. "I actually started working with Elmer’s before teaching," she laughs. “When you take that material and put it up on a wall, you’re almost begging for a destructive process ... It’s fascinating and beautiful and utterly human.” Hannah sees innumerable parallels between the destructive process in art, the deconstructive process of teaching, and the inherent balance of nature. Even with the simple act of mixing paint, “when we’re making a more beautiful green, we’re adding red to it.”

In the art classroom, Hannah finds culmination in all of the above. She gets: 1) dedicated time with students and materials; 2) to simplify her thought process; 3) lessons which are good counterpoints for her own work; and 4) the chance to watch a student go through their own creative process. “I try to model risk-taking, productive failure, and self-care as an educator.” She wants students to be comfortable with change, mistakes, and new experiences, all of which are underlying themes in her work. Having art be present at the time that a child matures, discovers their body and their own free will, starts to understand perception of color and form, is immensely important. Hannah stresses that her classes are fundamentally about discovering oneself, and oneself in the world. She teaches empathy, trust, sharing resources and materials, dialogue, giving and showing respect. In critiques, she avoids subjective comments. “The real critique starts after 'because',” Hannah says. These are lessons that apply to everyone, no matter which career path you choose.

Hannah is currently artist-in-residence at The Studios @ Mass MoCA. She is also participating in an upcoming show called Pathways: Monotypes and Artist’s Books, curated by Doris Madsen, at Elusie Gallery in Easthampton, MA. She is curating an upcoming show in August at the ECA+ Gallery, also in Easthampton, MA. Her portfolio, bio, and CV are available at her website: www.hannahrichards.org.

Article by Ivan Himanen, March 2017